Exhibitions in Singapore: Hermès houses artist Takashi Kuribayashi’s ‘Resonance of Nature’

Art Republik cover star Takashi Kuribayashi discusses his critical commentary on nature and how incidents in his native homeland helped shape his work

Hermès Singapore’s flagship store’s show window at Liat Towers displays Takashi Kuribayashi’s ‘Resonance of Nature’ till March 2017.

“The truth resides in places that are invisible. Once you are aware that there is a different world out of sight, you will be living in a different way,” says Japanese contemporary artist Takashi Kuribayashi, who reminds us of the philosophical dilemma of perception versus reality, and that the truth is only a matter of perspective.

No stranger to Singapore, Kuribayashi first visited the sunny island back in 2006 when he was invited to participate in the Singapore Biennale and Hermès Singapore’s previous Third Floor space; the former with ‘Aquarium: I feel like I am in a fishbowl’, and the latter with ‘Hermès Column’, both newly commissioned artworks. A year later in 2007, he came back again to suspend a small pond in mid-air at the entrance of the National Museum of Singapore with his work titled, ‘Kleine See’ (Small Pond). Then again in 2015, he created his unforgettably stunning and photogenic work, ‘Trees’, for Singapore Art Museum’s (SAM) ‘Imaginarium – A Voyage of Big Ideas’, which was displayed at SAM at 8Q. Now back again, Kuribayashi has created ‘Resonance of Nature’ for Hermès Singapore’s flagship store’s show window at Liat Towers, which will be on display till March 2017.

Installation view of ‘Trees’, at 8Q, Singapore Art Museum.

Art Republik catches up with our issue’s cover star to find out more about borders, serendipity and Kuuki ga Shimaru.

Your work often runs a critical commentary on nature. How and when did your relationship with nature and the environment come about? Was there a key moment for you?

I was born in Nagasaki, Japan, and lived there throughout my youth. And where I lived, around my house and all my surroundings were nature — you could even say that nature inevitably became like a teacher to me. What’s interesting also is that my father was a photographer of insects so his studio was out in the open. I was constantly surrounded by nature growing up — it naturally became a huge part of me.

What is it about nature and the environment that interests you?

As you know, humans can’t live by ourselves but yet we fear what nature can do to us; over time, we’ve found ways to ‘co-exist’ with nature. Humans first created a wall to protect themselves from nature; then they wanted to get closer to integrate with nature so they made parks and gardens; and now humans are so developed and capable that they want to overtake and disrupt nature. Before, nature was bigger than humans, but now, human development has gone too far to the extent that we are destroying nature; yet, we are still oblivious to that fact.

As an artist, what are your feelings towards taking nature and putting it in a man-made and enclosed gallery space? Does the act of doing this further emphasise your philosophies, messages and stories you want to tell? Or does this boundary or contradiction disturb you in any way?

To talk about this, we have to also talk about what art is. A good example of me taking nature out of its place and putting it in a gallery space is a work I made for an exhibition at Singapore Art Museum in 2015 where I literally took a whole tree and put them in boxes in an enclosed space.

As you know, Singapore is very artificial; even most of nature here is in a way created by man. In Singapore, people try to control nature by creating parks or creating space for something else, so that tree was already removed and chopped up for such a purpose, so I put all of it into glass boxes. This is a very symbolic work. You see this as one tree, but each box has created an individual world and new cycle of life for each piece of the tree. What I’m trying to do is make people think and be aware of what’s going on – that’s what art is; it should objectively encourage questions or provide awareness of something otherwise unaware of.

Inside of myself, there are two versions, two Kuribayashis so-to-speak: one is an artist, and the other is a human being. As a human being I want to protect nature, but as an artist, I want to objectively bring to surface certain truths.

So you think that being an artist and being a human being are separate?

Imagine a time when you are sad and you’re crying, and suddenly you feel like you are looking over, watching yourself cry; that other side or other view is the artist view.

Are you a spiritual person? Do you have a strong relationship with spirituality that you translate to your work?

No, I’m not. To me, being an artist is just I questioning myself, questioning the world, questioning things… an important question is: who am I? Most people do ask themselves that growing up till maybe their teenage years, but as an artist, I continue to ask myself that even into adulthood. So now what you have to think is: I’m here, I’m existing here. And you are here right now, but based on the people you have met in the past. The relationship becomes very important – you are created by the past. It may seem spiritual but it’s not. That said, I do believe anyone who has strong belief in their own respective religions, that aspect about them is not too different from me.

You’re currently based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Why did you choose to move there?

You’re going to say this is spiritual again but in my life, I have always trusted my intuition or gut feelings. I was previously in Japan for eight years, and before that 12 years in Germany. And then as you know on March 2011 (we call 311), it was the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. At that time I was thinking of getting out of Japan again, but the Fukushima incident happened, and I felt like I should stay in Japan; so I stayed for two years and so many unexpected things ended up happening in those two years.

After that, I thought I should get out and live outside Japan again. I was thinking Brazil at first because I have a good number of friends there and I like the Brazilian art scene. So I started researching moving to Brazil but all of a sudden, people around me started saying that I should move to Indonesia instead; at the time, I didn’t know much about Indonesia. Then as I got interested in finding out more, people started saying Yogyakarta, and I wasn’t even searching for that. Then an Indonesian collector calls me to present works in Yogyakarta. Another thing is that I surf, and one of my surfing friends told me out of the blue that there is a point in Yogyakarta called Pacitan for surfers. So again, I’m now hearing Yogyakarta from just about everyone around me. That was the moment I was convinced my next move had to be to Yogyakarta. I’ve been living there for three years now.

How did the Fukushima incident affect you personally and as an artist?

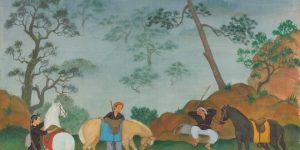

Work from the series, ‘Yatai Trip Project’

So the earthquake happened on 11 March 2011, and I was in Nepal in the mountains working on my ‘Yatai Trip Project’ until 10 March 2011. So on 10 March, 4,000 metres up in the mountains, pushing my Yatai food cart, I was just thinking to myself that we actually don’t need fuel energy to live. And then coming down and back to Tokyo, the incident happened. And I was back in Tokyo city still carrying all my backpacks and gear and everyone was just looking at me thinking I was so prepared but I actually just came back!

So for me, it was a chance for change. As a human being again, I was scared and should be getting far away; but as an artist, it was a chance to make something of this. As you know, my theme is borders, and the Japanese government created a 20-kilometre restricted area away from the nuclear plant, as a border. Now Japanese nuclear plants are all built near the coastlines because they require a lot of water. So while the border may extend on land, how do you create a border in the ocean? You can’t just draw a line. So as an artist, I thought, while the media focused on the 20-kilometre border on land, I would surf (yes, illegally) in the ‘restricted zone’ and highlight the unfelt or ‘invisible’ danger and damage done.

Of course, I consulted specialists and every one of them discouraged me from doing it, saying it was too dangerous. But the thing about plutonium is that it’s relatively safe to drink but not to breathe in where it will seriously damage your lungs. So if I really insisted on surfing in the restricted waters, I had to wear a protective suit with an air-filtration mask.

From afar, it looks like someone is surfing in beautiful waters. But if you look closely, that person is wearing a special wetsuit and protective mask. That’s the impact of the awareness of the message I am trying to convey. As artists, I feel it is our responsibility to report messages, almost like we are our own media outlets ourselves.

Takashi Kuribayashi, surfing in Fukushima.

You’ve been working with Hermès for 10 years now. What is it you like most about working with the brand?

Hermès has the highest standard and quality about them and their products, and when incorporated with or into my work, it gives off a sense of… there is a Japanese word for this: Kuuki ga Shimaru. It directly translates to tightening the air, or not so literally, straightens your back. It’s a very unique word that would also be used, for example, when you see a glass mirror instead of an acrylic mirror, your sense can feel the seemingly invisible but obvious difference.

Can you tell us more about your latest work with Hermès Singapore, ‘Resonance of Nature’, for their window display?

The lightning is the most important aspect of ‘Resonance of Nature’. I want to show the energy and power of nature all around us, so the lightning is the best representation that connects the air to the ground and below. At the same time, that power is present no matter the backdrop, no matter the time; it may be snowing in Japan and sunny in Singapore, but that energy and power is all the same. Hence the lightning in my artwork connects everything together – nature is connected everywhere.

Also, the background of the display is made up of key photos: the sky is from Fukushima, above the nuclear power plant; the seaside is from the tsunami aftermath; and the mountain side is of Nepal, where I was at until the day before the incident. This additionally shows the connection and importance of time, that although it is just a one-day difference, nature had the sheer power to change things so much.

Do you keep in mind the ethos of Hermès when conceptualising their window displays? Or is that something that comes about coincidentally if any at all?

Amongst all the other fashion brands today, Hermès has managed to keep itself in a unique position. We are currently in the midst of the consumption culture, and there are a lot of other brands that have opened a cheaper line to stay competitive. But if say sales for Hermès declines, would they also create a more affordable range? The answer is no, they will stay true to their values and DNA. And I believe show windows are faces of a brand, so the only thing I do keep in mind is to maintain that standard and outlook when thinking of my work for them.

If you weren’t an artist, what would you be?

I don’t believe being an artist is an occupation; it is just a way of living, a way of expressing one’s self. And what I am is simply Takashi Kuribayashi.

Takashi Kuribayashi: ‘To me, being an artist is just I questioning myself, questioning the world, questioning things…’

What’s next for you?

The upcoming year will start me off as a stage designer, joining the performance named ‘The World Conference’, directed by stage director Hiroshi Koike. Following, I will present my work at Zushi Beach Film Festival, Japan Alps Art Festival and group exhibitions in Yogyakarta. Besides that, I will continue my ‘Yatai Trip Project’, and I am also thinking of making research trips around Japan to develop new ideas for new works.

This article was first published in Art Republik.